Boyz n the Hood is the archetypal hood film. John Singleton’s 1991 directorial debut is the progenitor for a decade of films that would be defined as “hood films”. Spike Lee may have sparked the independent black movement with Do The Right Thing in 1989, but few movies have set the tone for an entire genre like Boyz n The Hood. The best part? It is a genre defining film in every sense of the word. The film tells the tale of a young black man Tre, who is raised in a tough California neighborhood in the mid-eighties through early nineties. The film touches on almost every aspect of the young black male psyche growing up in the LA ghettos, and is meticulously detailed because the writer and director, John Singleton, grew up on these very streets.

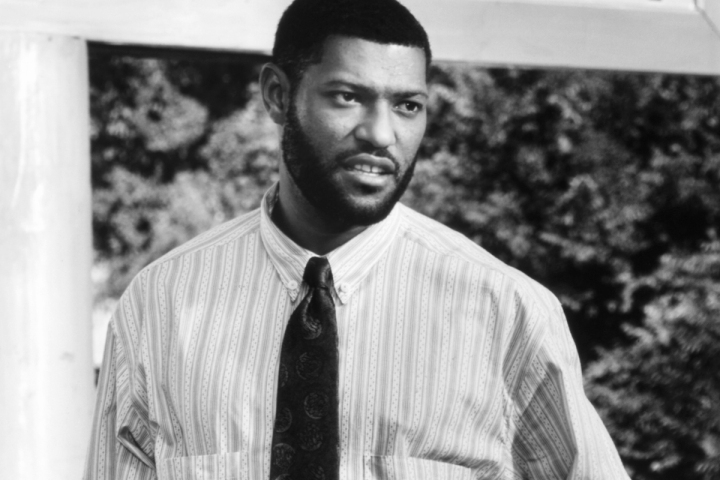

The film spends the entire time with Tre and his immediate family and friends whom we grow to know and care deeply about. Jason “Furious” Styles (Laurence Fishburne), instills important values to his young son Tre and we watch him grow into a responsible young man. Cuba Gooding Jr. plays the adult Tre Styles with natural ease, as he struggles to be a man in a dangerous alpha male neighborhood. The film also focuses heavily on the Baker family, the opposite end of the black familial spectrum. Brenda Baker raises of two sons by different fathers without a strong male role model in the home. One son, Doughboy (Ice Cube) falls prey to the life of crime and drugs, while the other, Ricky (Morris Chestnut), has a bright future as a football star. Each of our principal characters has depth and thus the tragedy at the heart of the film feels meaningful and is deeply upsetting. Unlike Tupac in Juice, Ice Cube’s Doughboy doesn’t feel like a caricature of a gangbanger or a gangster. He’s a decent person but he’s caught up in a life of drugs and violence that he can’t escape from, and the saddest part is he knows it. “Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what’s going on in the hood,” Doughboy’s depressing moment of clarity punctuates the film’s ending.

The film never feels overburdened by its powerful themes. First and foremost, the environment that these kids grow up in is toxic. Guns, drugs, and alcohol contribute to a cycle of violence that permeates through many minority neighborhoods. A simple act like brushing up against someone can have disastrous consequences. Petty arguments can turn deadly due to the testosterone fueled code of honor combined with readily available weapons. This is a place where you can go out for a walk and not make it back home alive. The police are abusive and horrific, especially the self-hating black police officer who harasses the characters and treats them like subhuman monsters.

Yet despite all the despair and violence, and as Roger Ebert said, police “acting as an occupying force”, there is hope in this film (Ebert). It may be an ember in a damp rainforest but still the film has hope. Furious Styles is a paragon of a strong black role model for his son. Furious teaches Tre how to be a responsible young man in the dangerous and uncaring world that they live in. He tells his son the “truth” about “the white man’s world”; how the army is no place for a black man, and how the “system” is only concerned with incarcerating blacks or content to allow them to destroy themselves while they profit from gentrification down the line. Surviving and escaping the ghetto is a key motivation for both Ricky and Tre. Besides the army, college is the next best way to escape. Ricky is a football star and hopes to get a scholarship to USC, while Tre hopes to get into college by using his keen intelligence. Yet even Tre, a character raised ‘right’, comes close to falling into the cycle of violence.

The direction by Singleton is simple but powerful, perfectly getting the slang of the hood and natural actions and mannerisms of his actors. For example, his lingering on shots like that of a bullet riddled Reagan/Bush poster, or how it's bookended by quotes describing the stark reality of the neighborhood he grew up in are superb. This is a character driven film and Singleton’s direction gives most of the characters room to develop and grow. We feel their frustration, their hopelessness, and their dreams as they try and escape the miserable place where they reside. Our antagonists aren’t portrayed as pure evil either (Ebert), and the horrifying realization that slowly begins to dawn on you is that they’re just other people within this culture of senseless violence. A lesser film would strain under the weight of these problems and issues, but Singleton handles them like a pro.

The only downside of a film with such a heavy focus on its male characters is in the treatment of its female characters. Certain subsets of black culture are extremely misogynistic, and that is not glossed over here in the dialogue. This blatant misogyny is brought up and mentioned as a problem, but it's never addressed, and many characters continue to treat the women badly. There are five female characters in the film, and three are mothers. In addition to Tre’s mother Reva, there is Brenda Baker, who has two grown children out of wedlock, and Ricky Baker’s girlfriend who has an infant also out of wedlock. Doughboy’s main girl meanwhile, is a beer swilling ‘hood rat’, who dislikes being called a bitch but seems to grudgingly accept her role as such. Tre’s love interest, Brandi, is at first held to an impossible ideal of pure womanhood, but she gives up her pure femininity so that the film can have a sex scene. The scene is awkward, and incongruous with her character, but palatable given Tre’s emotional and vulnerable state. The lack of strong female voices can be attributed to Singleton’s actual experiences in black communities. But that doesn’t excuse why there isn’t a strong black female character in the movie and why the women in the movie are primarily reduced to their sexuality.

Perhaps the biggest missed opportunity for a strong female character is Tre’s mother, Reva Devereaux (Angela Bassett), who should have been portrayed as a strong female character. Unfortunately, she all but disappears from the movie after a few scenes. She is in the process of obtaining her master’s degree, and decides to let Tre live with his father so he can teach him how to be a man. This is fine, but then as Tre ascends to adulthood, she is upset at her choice ostensibly because Tre is going to college with a female. Perhaps she is concerned that Tre and his girlfriend will end up like his parents, by having a baby out of wedlock at a young age, and thus have to work that much harder to achieve their own goals; but the film doesn’t address this clearly. After a scene where she yells at Furious for contrived reasons, she vanishes from the film. My point here is that her character could have been developed to coincide with Furious, as a strong female counterpoint voice of reason. Perhaps we could have seen Tre on one of his weekend visits with his mother learning different but still valuable information/lessons.

Boyz n The Hood will go down as one of the most important films of the nineties. Not only did it literally write the book for all other “hood films” that came after it but few others match the film’s maturity, depth, and narrative. In 2002 it’s significance was recognized by The Library of Congress, and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. The film exposes the deep wounds inflicted upon the black community by guns, alcohol, and drugs such as crack cocaine, but offers no easy solutions other than to escape. It’s themes and messages strike directly to the heart of the cultural and institutionalized problems of race within American society, problems that still affect minority communities to this day.

TLDR: Boyz n the Hood is an important and poignant coming of age tale about a group of friends in the ghettos of California in the mid-eighties to early nineties. 4.5/5 stars.

Ebert, Roger. "Boyz N the Hood Movie Review & Film Summary (1991) | Roger Ebert." www.rogerebert.com. Ebert Digital LLC, 12 July 1991. Web. Feb. 2016. <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/boyz-n-the-hood-1991>.